“Anyone who thinks they understand India is a fool,” an Indian Member of Parliament once remarked during an election. Having lived in both North and South India and traveled across all 28 states during my service, I fully resonate with this sentiment. I often find myself quietly amused by those who judge India solely based on what they see in the streets and overcrowded tourist spots. Even more amusing is how the international media fixates on slums and garbage whenever India is mentioned, despite the fact that India is the ‘Pharmacy of the World,’ a nuclear power, the first country to reach Mars on its maiden attempt, and the first to land a mission near the Moon’s south pole. India is also the fourth country with anti-satellite capabilities and the largest exporter of IT services globally. The Tom, Dick, and Harry who visit India for two weeks and then vlog about the chaos in its streets completely miss the bigger picture. India, in many ways, is organized chaos—far too intricate to be captured by any single narrative or framework.

To truly understand India, one must engage with its social, cultural, philosophical, and spiritual layers. The phrase ‘Unity in Diversity’ is a lived reality for over a billion people, practiced daily in both subtle and profound ways. In a world where globalization often deepens cultural divides, India stands as an exemplary model of how cultural intelligence can navigate intricate socio-economic landscapes.

While Europe plays politics with refugees from regions it has destabilized, India has embraced vulnerable communities with compassion. Around 72,000 Tibetans, arriving after the Dalai Lama’s 1959 exile, were granted asylum and supported through settlements, schools, and self-employment programs to preserve their culture, the 57,000-strong Parsi community, present for over a millennium, has retained its Zoroastrian identity while contributing to India’s trade, philanthropy, and industry, seamlessly integrating into the socio-economic fabric.

With a population of 1.4 billion, making up 17.39% of the global population, India is one of the most geographically and ethnically diverse nations in the world. To put this into perspective, the European Union, comprising 27 countries, has a population of around 450 million—India, with its 1.4 billion people, is more than three times as populous as the entire EU.Unsurprisingly, Indian communities are found across the globe, their presence expanding in tandem with the country’s rising Purchasing Power Parity (PPP). The country boasts 22 official languages and over 1,600 dialects, spoken across its diverse regions.

During one of my trekking trips to Spiti Valley in the Himalayas, I met two Portuguese trekkers, a father and son. The father, around 70 years old and a frequent visitor to India, summed it up perfectly: ‘India is not just a country; it’s more like a continent.’ India is home to over 2,000 distinct ethnic groups, each with its own unique traditions, cuisine, attire, and way of life. From the Aryan descendants in the north to the Dravidian-speaking communities in the south, from the indigenous tribes of the northeast to the nomadic peoples of the deserts, and the Mongoloid and Negrito groups in the Andaman Islands, India’s ethnic diversity reflects the richness of its cultural heritage.

In terms of religion, 79.8% of India’s population follows Hinduism, 14.2% adhere to Islam, 2.3% to Christianity, 1.7% to Sikhism, 0.7% to Buddhism, and 0.4% to Jainism. Hinduism, along with other interconnected religions like Buddhism, Jainism, and Sikhism, emphasizes the cyclical nature of existence, known as samsara, which involves the cycle of birth, death, and rebirth. The ultimate goal is liberation (moksha or nirvana), attained through one’s actions (karma) over multiple lifetimes. In contrast, Semitic religions such as Islam, Christianity, and Judaism adopt a linear perspective on life, where the soul is judged after death and directed to either heaven or hell based on one’s faith and deeds during their singular lifetime. This fundamental distinction between the Dharmic traditions and Abrahamic faiths shapes their unique worldviews, influencing how their followers perceive life, work, and the concept of destiny.

India’s social structure has historically been shaped by the caste system, comprising the Varna and Jati systems. Initially, these systems assigned social roles based on an individual’s qualities and actions, but over time, they became rigidly tied to birth—a concept that can be culturally shocking for many. The Varna system was first introduced in the Rigveda (circa 1500–1200 BCE), particularly in the Purusha Sukta hymn (Rigveda 10.90), which describes the creation of the four varnas: Brahmins (priests) from the mouth, Kshatriyas (warriors) from the arms, Vaishyas (merchants) from the thighs, and Shudras (laborers) from the feet. The Bhagavad Gita (400 BCE–400 CE), particularly in Gita 4.13, emphasizes that one’s duties (dharma) should be determined by qualities and actions (guna and karma), rather than by birth. However, the Manusmriti (2nd century BCE–3rd century CE) later codified the Varna system more rigidly. Manusmriti 1.31 reaffirms the birth-based creation of the four varnas from Brahma’s (God’s) body parts, while Manusmriti 10.4 stipulates that only the first three varnas (Brahmins, Kshatriyas, and Vaishyas) undergo a second spiritual birth, whereas Shudras do not, thereby reinforcing their lower social status.

This rigid, hereditary caste system became deeply ingrained in Indian society. Another group, the Dalits (formerly referred to as ‘Untouchables’), was excluded from the Varna system altogether and relegated to performing tasks considered impure by the upper castes, facing severe social exclusion. Such exclusionary systems were not unique to India; similar practices existed elsewhere, such as in apartheid-era South Africa, where institutionalized racial segregation and discrimination persisted until the system’s formal end in 1994.

The table below provides an approximate snapshot of India’s demographic composition, illustrating how each religious group is divided, with a particularly large portion of the population concentrated in the lower strata of the Hindu social hierarchy.

In developed countries like Norway, Germany, Denmark, Finland, Sweden, individuals working in low-skilled jobs—such as janitors, construction workers, or farm laborers—experience conditions that starkly contrast with those of workers in similar professions in India. The disparity in living standards is so pronounced that it can be quite embarrassing by comparison. Low-skilled workers in India often endure much harsher living conditions, face significant social disadvantages, and carry the burden of entrenched social stigma, further marginalizing them in society.

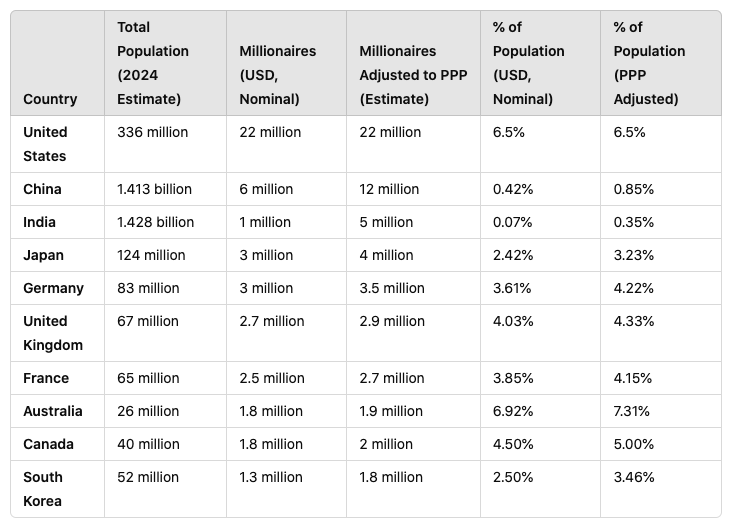

India’s economic classification divides society into low, middle, and high-income groups, each characterized by distinct consumption patterns, living standards, and access to essential services. Purchasing Power Parity (PPP) is a key metric for comparing income levels globally, as it adjusts for local living costs, providing a more accurate cross-country comparison. The table below highlights the disparities in income and inequality across different social groups, while also reflecting the significant number of wealthy individuals in the country.

For high-net-worth individuals, classifications based on nominal U.S. dollars and Purchasing Power Parity (PPP) provide revealing insights. When measured in nominal USD, the number of millionaires in India includes those whose wealth exceeds $1 million, without adjusting for local cost differences. However, when wealth is adjusted for PPP, the number of millionaires increases significantly, highlighting the substantial impact of India’s lower cost of living.

Based on UN estimates and other population data sources, around 45 countries have populations under 5 million. These comparisons offer valuable perspective when examining India’s diverse economic landscape, where income disparities are pronounced, and the country’s immense population magnifies the number of individuals across all economic levels—from those living in poverty to millionaires.

Let’s take a closer look at homeownership rates in India and compare them with those of other nations. Data from 12 countries reveal significant global variations. Romania leads with an impressive 96.8% homeownership rate, while Switzerland ranks the lowest at just 42.5%. The United Kingdom (65.5%) and the United States (65.8%) fall within the mid-range, whereas countries like Slovakia (92.3%), Singapore (90.4%), and India (86.6%) report notably higher levels of homeownership. These disparities highlight how cultural traditions, economic policies, and housing markets shape homeownership rates across different nations.

India’s education system during the Mughal era (1526–1857) was diverse, featuring madrasas and maktabs for Muslims and pathshalas, tols, and gurukulas for Hindus, primarily serving the elite. However, with British colonial rule (1857-1947), a Western-style education system was introduced, emphasizing English and secular learning, which led to the marginalization of traditional institutions. This shift in focus meant that while upper-class urban families gained access to English education, the rural poor, lower castes, and tribal communities were largely excluded. After independence, the Indian government recognized education as a critical tool for social mobility and nation-building. To address historical caste-based discrimination, a reservation system was introduced to provide greater access to education for marginalized groups, such as Scheduled Castes (SCs) and Scheduled Tribes (STs), particularly in government institutions.

The establishment of the Indian Institutes of Technology (IIT) in 1951 and the Indian Institutes of Management (IIM) in 1961 represented a turning point in India’s development, significantly shaping the nation’s global influence by cultivating world-class talent across various fields. These prestigious institutions have consistently produced highly skilled professionals, many of whom have ascended to leadership positions in multinational corporations as CEOs and top engineers. Furthermore, the rapid expansion of India’s service sectors, particularly in software and IT during the 1990s, greatly accelerated economic growth and fostered social mobility.

Despite these achievements, one might wonder why China has experienced faster economic growth, higher Human Development Index (HDI) scores, and more advanced infrastructure compared to India. A significant factor lies in the differences between their governance systems. China’s non-democratic model, which blends state capitalism with communist rule, has enabled swift and centralized decision-making. This was particularly evident after the economic reforms of the 1990s, which are credited with lifting approximately 800 million people out of poverty—a transformation often referred to as the “miracle of the century.” China’s political stability, streamlined governance, and relatively homogeneous population have been key drivers of its rapid development. These factors have allowed the government to efficiently implement large-scale economic strategies and infrastructure projects, contributing to the country’s remarkable growth trajectory.

On the international stage, India has consistently been a nation that prioritizes peace over aggression. Despite having the fourth most powerful military in the world—after the U.S., Russia, and China, according to the Global Firepower Index—India continues to favor diplomacy over escalation. The philosophy of Ahimsa (non-violence), deeply rooted in Indian religious culture, serves as a guiding principle for India’s global interactions.

India has also earned the title of the “Pharmacy of the World” due to its capacity to produce affordable generic medicines. During the COVID-19 pandemic, India played a pivotal role in developing and distributing vaccines that were crucial for global vaccination efforts. The Serum Institute of India (SII), the world’s largest vaccine manufacturer by volume, significantly contributed to this initiative through India’s Vaccine Maitri program, supplying vaccines to over 90 countries, including those in South Asia, Africa, Latin America, and the Caribbean. While India actively shared its vaccines with the world, many Western countries initially focused on securing vaccines for their own populations, leading to criticisms of vaccine nationalism.

As of 2023, the Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO) has launched 431 satellites for global customers from 34 countries, establishing itself as a significant player in the global space industry. In defense, India has developed a formidable nuclear triad, including the INS Arihant, and advanced missile systems like Agni-V and BrahMos. The country also demonstrated its anti-satellite (ASAT) capabilities with Mission Shakti in 2019, further strengthening its strategic defense posture.

Additionally, India’s digital landscape has been revolutionized by initiatives like Aadhaar and Unified Payments Interface (UPI), positioning the country as a leader in IT services and financial technology, with cities like Bengaluru and Hyderabad emerging as global IT hubs.

Despite these advancements, the country continues to face significant challenges in sanitation and inadequate infrastructure, particularly among the lower-income groups, which make up nearly one-third of the population. Having experienced both the structured life within Air Force townships and the chaos outside, I have witnessed both sides of this reality. Social behavior and discipline remain major areas of concern, often marked by a noticeable lack of public etiquette, largely due to inadequate education at the grassroots level.

When people ask me when India will overcome these challenges, I often respond, “Sambhavami Yuge Yuge,” a Sanskrit phrase meaning “I come into being age after age.” This reflects a broader cultural perspective, where many may not feel an immediate urgency to address these issues, viewing life as a cyclical journey. This sentiment is echoed in Chapter 2, Verse 27 of the Bhagavad Gita, which states: “For one who is born, death is certain, and for one who has died, birth is certain; therefore, you should not lament over the inevitable.” Additionally, Chapter 2, Verse 47 advises: “You have a right to perform your duty, but not to the fruits of your actions. Never consider yourself the cause of the results of your activities, nor be attached to inaction.”

Leave a comment