The world continues to reap the chaos sown by the British Empire.

In Kashmir, the British left a bleeding wound during the partition of India and Pakistan, fostering a border dispute that has fueled conflict between the two nations, claiming thousands of lives since 1947.

In Palestine, they established a European settler colony, positioning it to dominate the Middle East. The region has endured wars linked to this legacy—in Afghanistan, Iraq, Libya, Sudan, Lebanon, Syria, and Palestine—claiming millions of lives since 1948.

In Hong Kong, they left behind a thriving cosmopolitan hub that remains neither fully independent nor wholly integrated with mainland China. The 1.4 billion Chinese people still recall the “Century of Humiliation,” when the British forced opium on China—a stark symbol of imperial greed and exploitation.

The British lowered their Union Flag and departed, leaving a ruinous legacy that continues to haunt generations. These consequences are not mere relics of the past—they unfold daily, with the blood of innocent women and children still being shed.

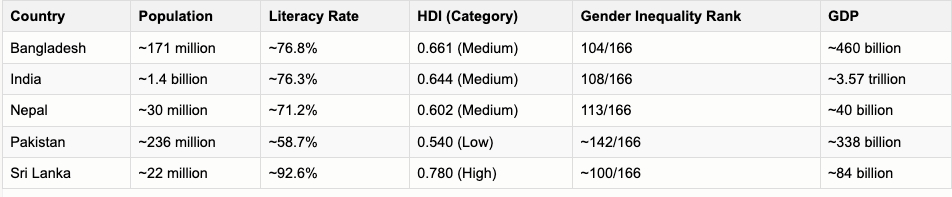

That said, this history does not excuse the current state of South Asian countries, which I call the “Five Idiots”—India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, and Nepal. Modern genetic studies reveal that these nations share a common ancestry: the Ancestral South Indians (ASI) and Ancestral North Indians (ANI) form the foundational genetic groups of the subcontinent. Migration patterns over millennia, including those of Indo-Aryans, Dravidians, and later groups such as Turks, Persians, Arabs, and Europeans, have shaped the region’s genetic diversity. Yet, despite this genetic mix, shared geography, history, and culture—representing a quarter of the world’s population—these nations rank among the lower tiers of the Human Development Index.

A land celebrated for its unity in diversity is now fractured by religion, caste, borders, and languages, squandering its vast reservoir of talent. India, once a secular liberal democracy, has veered toward far-right Hindu nationalism, while Pakistan—a failed state by nearly all metrics—remains mired in corruption, tribal divisions, and religious extremism. In India, mobs waving saffron flags desecrate churches and mosques in public, while the police, tasked with ensuring safety and security, stand by and watch. Meanwhile, in Pakistan, a facade of military-backed democracy persists, yet the country remains deeply divided along ethnic lines among Punjabis, Balochis, Pashtuns, Sindhis, and others. Despite its self-proclaimed status as an Islamic republic, Pakistan continues to grapple with internal strife fueled by sectarianism and governance failures.

Pakistan’s current state of affairs is so dire that it brings shame not only to its own citizens but also to the 220 million Indian Muslims, a population nearly equivalent to Pakistan’s, for the failure of this Islamic republic. If Pakistan’s founders sought independence from Mother India, why didn’t they build a thriving nation like Malaysia or Indonesia? Instead, Pakistan has become a dysfunctional, corrupt, and divided country, so much so that far-right Hindu nationalists in India mock Indian Muslims, telling them to “go to Pakistan.” With a completely corrupt military and political system, this country cannot sustain itself unless a revolution transforms it entirely and dethrones the military oligarchy that thrives on the India-Pakistan enmity lullaby.

Having traveled to Bangladesh, I found it to be one of the most disorganized nations I’ve visited, plagued by poor infrastructure and widespread poverty. The rise of anti-Muslim rhetoric in India has fueled anti-Hindu rhetoric in Bangladesh, exacerbating social tensions.

Sri Lanka, a country I have traveled to and admire for its geographical beauty, is a struggling state. Decades of conflict between Tamils and Sinhalese have left the nation reliant on debt, hampering its stability.

Nepal, close to my heart for its Himalayas and trekking, ranks among the poorest countries according to UN statistics, lagging in innovation and development outside of tourism. Over three visits spanning five years, I saw no meaningful progress in its cities or overall development.

What does the above data reveal about these countries? Despite collectively representing one of the world’s largest markets, with nearly a quarter of the global population, these nations remain far from achieving true prosperity and substantial improvements in their Human Development Index (HDI).

Consider China, a country with 1.4 billion people, where 80% of the population lived below the poverty line in the 1990s. Today, China is the second-largest economy in the world, a global powerhouse with the highest GDP and the lowest poverty rate—just 0.2% of its population, the lowest in the world.

In India and Pakistan, the Kashmir conflict is often less about resolution and more about political survival. According to the South Asia Terrorism Portal (SATP), India suffered approximately 21,789 fatalities from 2000 to 2024, while Pakistan recorded around 174,201 fatalities in the same period due to internal instability. Pakistan’s higher casualty count is attributed to intense militant insurgencies, particularly in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Balochistan. In contrast, India’s fatalities are primarily concentrated in Jammu and Kashmir, with notable incidents like the 2025 Pahalgam attack, which claimed 26 innocent civilian lives.

The Kashmir issue, a decades-long dispute between India and Pakistan over Jammu and Kashmir, threatens regional stability, raises human rights concerns, and carries the potential for nuclear escalation. The conflict originated in 1947 during the partition of British India, when the princely state of Jammu and Kashmir—ruled by a Hindu Maharaja but with a Muslim-majority population—became a point of contention.

The partition plan, implemented through the Indian Independence Act of 1947, allowed princely states to choose accession to either India or Pakistan. However, no clear guidelines were provided for states with mixed populations, such as Kashmir, where the ruler’s religion did not align with that of the majority. This ambiguity set the stage for conflict.

The Maharaja’s accession to India under controversial circumstances triggered the first Indo-Pakistani War (1947–48). Since then, India and Pakistan have fought multiple wars (1947–48, 1965, 1999) and maintain a heavily militarized Line of Control (LoC), dividing the region. The conflict has caused significant loss of life, widespread human rights abuses, and economic disruption.

A referendum has been proposed based on the UN Charter’s principle of self-determination (Article 1(2)) and UN Security Council Resolution 47 (1948), which called for a plebiscite to allow Kashmiris to decide their future—whether to join India, Pakistan, or potentially seek independence. However, implementation stalled due to disagreements over demilitarization and shifting regional dynamics. Adopted on April 21, 1948, UN Security Council Resolution 47 outlined a three-step process to resolve the issue:

- Pakistan’s Withdrawal : Pakistan was to withdraw all its nationals and tribesmen who entered Jammu and Kashmir for fighting, ensuring no further support for such incursions.

- India’s Force Reduction : India was to progressively reduce its military presence in the region to the minimum level required for maintaining law and order.

- Plebiscite : Once these conditions were met, a free and impartial plebiscite was to be conducted under UN supervision, enabling the people of Jammu and Kashmir to determine their future.

The revocation of Jammu and Kashmir’s special status (Article 370) by India in 2019 intensified local unrest and drew renewed international attention, including discussions at the UN Security Council.

What is the solution? If both countries cannot move forward on their own, the UN Charter should be firmly implemented as both India and Pakistan oppose the full implementation of the UN resolution on Kashmir due to their deeply entrenched positions.

India’s apprehension about losing territorial integrity is unfounded, as historical and socio-economic realities indicate that Muslims in India, including those in Kashmir, would never align with a failed state like Pakistan. Furthermore, holding a transparent and credible plebiscite would dismantle Pakistan’s justification for its proxy war tactics, thereby reducing regional tensions and fostering stability.

The leaders of these five South Asian nations must recognize that neighbors are irreplaceable and that their potential for prosperity lies in cooperation rather than conflict.

The possibilities for regional collaboration in South Asia are immense, with data-driven strategies offering clear pathways to progress. A military alliance akin to NATO or CSTO could significantly enhance regional security by fostering intelligence sharing and counterterrorism efforts, particularly given the staggering human cost of terrorism. Such an alliance could also reduce the financial burden of military expenditures freeing up resources for development.

Economically, regional trade agreements hold the potential to transform intra-South Asian trade, which remains abysmally low at just 5% of total trade under SAARC, compared to over 60% in the EU. With a combined GDP of approximately $4.5 trillion, deeper economic integration could catalyze unprecedented growth and job creation.

Additionally, technology transfer initiatives could elevate Human Development Index (HDI) scores—currently 0.670 for Bangladesh and 0.601 for Nepal (2023 UNDP)—by enabling innovations in sectors like IT and hydropower. These collaborative measures, supported by hard data, underscore the region’s untapped potential to address shared challenges and achieve sustainable prosperity through unity and cooperation

Leave a comment